Art as a Mirror of Its Time

Art is never created in isolation. It is deeply shaped by the historical, cultural, and political environment in which it emerges. Whether subtle or overt, art absorbs the values, tensions, and aspirations of its time becoming a powerful reflection of society.

Context is Everything

To understand a piece of art, one must consider the era in which it was made. The social mood, political structures, and technological advancements influence not only what is depicted but also how and why it’s expressed.

Visual Echoes of Politics and Protest

Throughout history, artists have responded to the world around them, expressing dissent, endorsing ideologies, or sparking debate:

Propaganda: Used by empires, dictatorships, and world powers to shape public opinion (e.g., Soviet posters, WWII American war art).

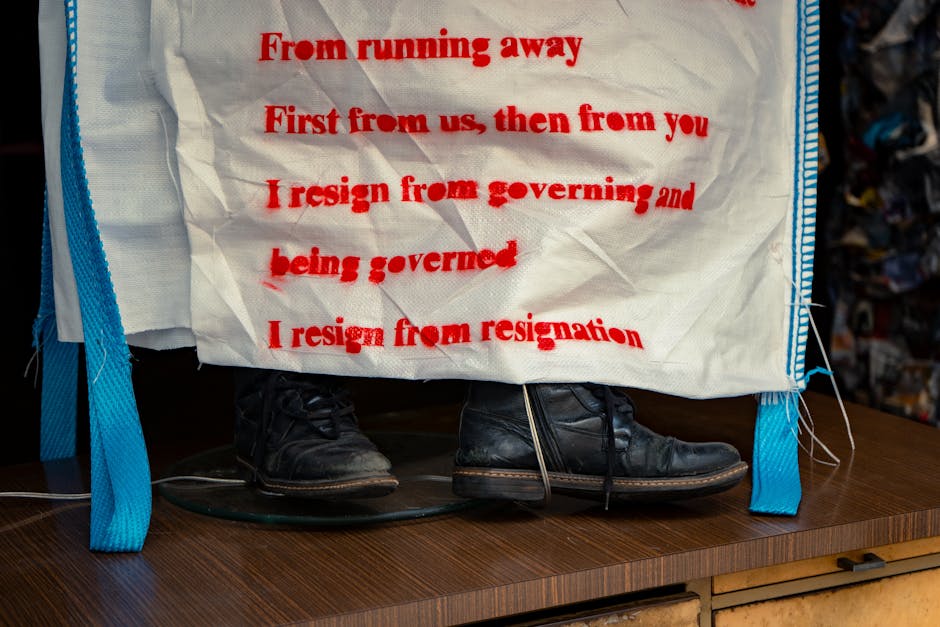

Protest Art: A tool for marginalized voices and social movements, such as anti Vietnam War posters or feminist art in the 1970s.

Public Murals: From Rivera’s Mexican murals to contemporary street art in cities like São Paulo or Belfast, murals often reflect collective identity and resistance.

The Artist as Observer and Critic

Artists have often straddled the line between reflecting society and challenging it. Whether through celebration or satire, they:

Capture history in motion

Amplify underrepresented voices

Hold a mirror up to power and cultural norms

In times of societal tension, artists may become visual historians, political commentators, or cultural agitators. Their work provides not only aesthetic value but also critical insight into prevailing ideologies and hidden truths.

Power, Politics, and the Paintbrush

Art has long been a tool for those in charge. Kings and emperors sat for grandiose portraits designed to project dominance and divine right. Think Louis XIV in full regalia or Augustus cast in godlike marble. The message was simple: look upon these images and understand who holds the reins. Fast forward to the 20th century, and regimes like Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy took it further with massive architecture, rigid realism, and visual excess all aimed at myth building. These weren’t just buildings or statues. They were propaganda ideology cast in stone, paint, and bronze.

But art doesn’t just serve power. It fights it, too. Revolutionary and countercultural movements have used visual expression as a weapon of defiance. During the French Revolution, allegorical paintings turned monarchy into target practice. Dadaists in post WWI Europe mocked the absurdity of nationalism with nonsense and collage. In 1960s America, artists created powerful visuals for the Civil Rights Movement posters, murals, collages all of it challenging brutality and systemic injustice through beauty and fury.

And then there’s the quiet kind of protest the slow burn. Symbolism, satire, and coded narratives have carried subversive messages past censors for centuries. A flower in the wrong season, a reversed flag, a smirking figure in the background details that speak loudly if you know how to listen. When speech is punished, the paintbrush whispers instead. Some of history’s most daring resistance lives not in pamphlets, but in paintings.

Social Hierarchies and Representation

Art history isn’t just about aesthetics it’s about who’s seen, how they’re shown, and who gets to do the showing. Race, gender, and class have long influenced not just the art itself, but the entire ecosystem around it. Who has access to training? Who owns the tools, the galleries, the commissions? These questions aren’t new, but they’re baked into every portrait, landscape, and mural we inherit.

For centuries, Western art favored white, male, upper class subjects and creators. Women were muses, not makers. People of color were often absent, exoticized, or stereotyped. Working class life? Occasionally romanticized, rarely dignified. The power dynamic was crystal clear: the gaze belonged to one group, and that gaze shaped reality on canvas and in sculpture.

In recent decades, marginalized artists have started reclaiming that narrative. Artists are depicting their own communities, telling their own stories, and challenging old standards of beauty, success, and truth. It’s less about fitting into existing frameworks, more about building new ones. And viewers have to adjust, too learning to question who’s behind the image and what they’re really being asked to see.

Ownership of narrative is as much a political act as a creative one. Every brushstroke, every frame, becomes a way to confront who gets to speak and who’s expected to stay silent.

When Religion Meets Politics in Art

Throughout history, religious imagery hasn’t just been about faith it’s been strategic. Kings, emperors, and even elected leaders have leaned into spiritual symbolism to legitimize their power. A halo above the crown, a divine looking gesture, or a stained glass window casting God’s light on authority none of that is by accident.

From Constantine’s fusion of cross and crown in Roman iconography to the divine right portraits of European monarchs, religion and power have marched shoulder to shoulder. Even revolutions co opted religious symbolism. Think of liberation theology imagery in Latin America or how ancient symbols were reframed during colonial resistance in Africa and South Asia. The art didn’t just reflect faith it carried layered political meaning.

Over centuries, as institutions changed, so did the visuals. Iconoclasm disrupted the old language; new regimes either erased the past or reinterpreted spiritual themes to assert their own ideologies.

For a deeper exploration of how these visuals evolved in tandem with shifting power structures, check out The Evolution of Religious Iconography Through the Ages.

Art in the Digital and Global Age (2026 and Beyond)

The gallery wall has cracked open. Today, art lives in pixels, shared timelines, and protest banners printed at home. Memes carry political weight just as much as a mural on a city block. Digital artists use open source tools and decentralized platforms to bypass traditional gatekeepers no curator, no institutional approval, just the work and its audience. It’s raw, fast moving, and often more honest.

Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and X (formerly Twitter) have turned activism into a visual loop: photos from protests become symbols, slogans become typeface art, and viral videos push marginalized narratives into mainstream feeds. In this mix, everyone grabs the megaphone. Whether you’re remixing a Banksy or drawing power from Indigenous symbology, the line between artist and critic blurs. People aren’t just observing culture they’re shaping it in real time.

Globally, you see this shift in the themes emerging from digital creators. A climate march in Sweden sparks animations in Johannesburg. Police violence in one city echoes through augmented reality street art in another. The reach and speed flatten borders, while still honoring local stories. Contemporary art today isn’t just a reaction it’s a networked, evolving dialogue shaped by anyone with a connection, a message, and the will to share.

Why This Still Matters in 2026

Art as a Lens Into Society

Art offers more than aesthetic value it’s a framework for interpreting the world around us. By understanding the visual language of different eras, viewers can gain insights into the values, fears, and politics that shaped those times.

Art reveals underlying social tensions and movements

It documents marginalized voices and dominant ideologies

Every brushstroke, medium, or motif is a clue to broader cultural dynamics

A Living Dialogue Between Art and Society

As societies evolve, so too does artistic expression. In 2026, artists are responding to global crises, emergent technologies, and shifting identities in real time. Whether it’s protest art shared online or public sculptures that challenge historical narratives, art remains a dynamic tool of communication and critique.

Visual media now reach larger and more diverse audiences

Artists move fluidly between activism, storytelling, and documentation

The line between creator and commentator continues to blur

Final Takeaway: The Power of Observing Art

To study art is to study the forces that shape us. Art history isn’t only about technique or beauty it’s about power, identity, resistance, and change. The deeper we look, the more we understand about our shared human experience.

Art reveals who we are, what we value, and where we’re headed

Cultural literacy through art empowers more informed citizenship

Every generation leaves a visual imprint decoding it helps shape a better future