Ancient Beginnings

Long before temples or scriptures, early humans were already looking upward and inward for meaning. They didn’t have formal religion, but they had symbols. In prehistoric cave art, we see handprints, animals, and geometric forms circles, spirals, and lattices etched into stone with intent. These weren’t mere decorations. They were markers of mystery, hints at belief systems not yet written down. The recurring use of animals, from bison to birds, suggests a spiritual reverence, or at the very least, a symbolic connection between the human and natural worlds. Patterns like concentric circles may have hinted at cosmologies, or early ideas of cycles and the divine.

As the first civilizations emerged, the spiritual grew more structured. In Mesopotamia, Sumerians honored gods who governed everything from rivers to writing and portrayed them in layered iconography. The ziggurat was more than engineering; it was architecture with cosmic purpose. Egypt took this further, intertwining divine and political power. Pharaohs stood tall as living gods, and their visuals ankhs, scarabs, falcons carried dense symbolic weight. Shapes and proportions in temple design weren’t random; they were sacred calculations.

Meanwhile, the Indus Valley civilization, though still mysterious, hinted at godlike figures surrounded by animals and ritual postures. Seals depicting horned deities, yogic stances, and abstract patterns suggest a rich symbolic vocabulary. Across these early cultures, two things held constant: that the divine could be signified through form, and that the physical world was a canvas for spiritual order.

Sacred geometry and animal symbolism weren’t just artistic choices they were tools to make the unseen feel present, to bridge the gap between gods and mortals, sky and soil.

Classical Civilizations and Syncretism

Greco Roman Influence on Religious Representations

As ancient Greece and Rome expanded their cultural and political reach, their religious iconography left a lasting impact on the visual language of the sacred. Temples, sculptures, and pottery depicted gods in human form idealized, noble, and often in mid action establishing a visual standard that endured for centuries.

Greek statues emphasized balance, proportion, and divine beauty

Roman art brought realism, narrative reliefs, and state sanctioned imagery

Deities were often tied to civic power, warfare, and nature’s order

Blending of Myths and Iconography

One defining trait of the classical world was its openness to syncretism the merging of gods, stories, and symbols across cultures. As empires grew, so did the fusion of spiritual traditions.

Greek and Roman gods were frequently equated with local deities (e.g., Zeus with the Egyptian Amun)

Temples incorporated regional myths while maintaining classical stylization

Symbols like the laurel wreath, cornucopia, and thunderbolt traveled far beyond their cultural origins

This blending enriched religious practices and allowed art to serve both devotional and diplomatic functions.

From Symbolic to Anthropomorphic Deities

Earlier civilizations often used abstract representations like sacred animals, geometric forms, or natural elements to symbolize divine forces. Classical civilizations humanized the divine, portraying gods with emotions, stories, and flaws.

Anthropomorphism brought gods closer to human experience

Emotional depth and narrative helped followers relate to the divine

Art became not just a reflection of doctrine, but a storytelling medium

This shift allowed for the flourishing of mythological scenes in public art and set a foundation for later religious traditions to explore the human divine connection through visual means.

Iconography under Judaism and Early Christianity

When monotheism began to take hold, especially within Judaism and early Christianity, visual representation entered contested territory. Judaism enforced a strict aniconic tradition, grounded in the Second Commandment’s prohibition of graven images. To avoid idolatry, Jewish art leaned heavily on symbols like the menorah, shofar, and pomegranate visual cues that hinted at the divine without attempting to depict it. The message was clear: God was too vast to be captured in material form.

Early Christianity inherited this tension but took a slightly different route. At first, Christians followed similar aniconic tendencies, particularly under Roman persecution. But as pockets of believers grew, so did the need for shared, visual language especially for a largely illiterate population. Enter the catacombs: hidden burial tunnels beneath Roman cities where frescoes began to appear. These weren’t idle decorations. They told stories Daniel in the lion’s den, Jonah and the whale, the Good Shepherd. Not portraits but metaphors, built to comfort and instruct.

This period didn’t resolve the image debate, but it laid the groundwork for Christian art as both narrative tool and theological battleground. The compromise was subtle but effective use images not as idols, but as symbols. Understand their meaning, not just their form. It was visual storytelling with restraint.

Byzantine Brilliance and the Power of the Icon

![]()

Religious imagery reached new theological and political significance in the Byzantine Empire, where art was more than decoration it was a form of communication between the divine and the faithful. The Eastern Roman Empire crafted a powerful visual theology that shaped religious practice and imperial identity for centuries.

The Dual Role of Icons: Political Power and Spiritual Presence

Byzantine religious art wasn’t just seen inside churches it permeated court life, public spaces, and symbols of sovereignty. Images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints reinforced the emperor’s divine right to rule, acting simultaneously as spiritual intercessors and tools of statecraft.

Icons served diplomatic and ceremonial functions, often presented as gifts between courts

Mosaics and frescoes adorned both palaces and churches, erasing the boundary between the sacred and the secular

Imperial patronage of religious art helped legitimize authority and unify diverse regions under one religious vision

The Rise of the Iconostasis and Artistic Codification

By the 6th century, religious imagery became increasingly systematized. Churches introduced the iconostasis a screen or wall filled with icons to separate the sanctuary (the holiest part of the church) from the nave, visually expressing the divide between heaven and earth.

A formal visual hierarchy emerged: Christ and the Virgin at the center, surrounded by saints and angels

Gold backgrounds and frontal poses emphasized the timeless, otherworldly presence of the holy figures

Icon painters followed strict canons, treating their work as a sacred calling, not artistic invention

The Crisis of Iconoclasm: Images Under Siege

However, not everyone accepted the power and presence of religious images. The 8th and 9th centuries saw waves of iconoclasm, a theological and political movement against the veneration of icons.

Critics accused icons of idolatry, arguing that depicting the divine diminished its transcendence

Under Emperor Leo III, thousands of icons were destroyed or painted over in churches and monasteries

Defenders of icons, like St. John of Damascus, argued that Christ’s incarnation justified visual representation “what is not assumed is not redeemed”

The eventual restoration of icons marked a major turning point, leading to celebrations like the “Triumph of Orthodoxy”

Byzantine art after iconoclasm became even more codified, devotional, and symbolically rich as if to protect what had nearly been lost. The result was a striking tradition that continues to influence Orthodox Christian art to this day.

Medieval Europe: Patronage and Piety

In medieval Europe, the Church wasn’t just a spiritual authority it was the single most powerful patron of the arts. Cathedrals, monasteries, and parish churches became the canvas on which faith was made visible. Art wasn’t decoration it was doctrine.

Much of the population couldn’t read, so the Church used visuals to teach. Stained glass windows told biblical stories in color and light. Frescoes covered every inch of chapel walls. Altarpieces framed holy scenes in gold leaf, guiding the eye and the soul toward theological truths. These weren’t just artistic achievements; they were tools of education and devotion.

Pilgrimage art also played a massive role. Relics of saints bones, clothing, fragments of the cross drew travelers from across the continent. Artists crafted reliquaries designed to awe and inspire. Pilgrimage routes became arteries of both spiritual and cultural exchange.

The Church, flush with tithes and land, funded this system with purpose. Art reinforced belief, consolidated influence, and brought the divine closer to the daily lives of the faithful.

(See more on power and art: Understanding Patronage The Role of Wealth in the Creation of Masterpieces)

The Renaissance: Humanizing the Divine

The Renaissance marked a profound transformation in religious iconography, moving away from rigid symbolism and toward a more natural, emotionally resonant form of visual storytelling. This era reflected not just a shift in technique, but a deeper philosophical engagement with the divine.

From Symbol to Sentiment

Artists began portraying religious figures with human emotions and realistic postures.

Biblical scenes featured ordinary people in relatable expressions of awe, grief, and joy.

The goal: to make the sacred more accessible and emotionally powerful for everyday viewers.

Masters Who Reshaped the Divine

Three iconic artists of the High Renaissance led this transformation:

Michelangelo

His frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, especially The Creation of Adam, introduced a dynamic, almost cinematic vision of divine creation.

Sculptures like the Pietà brought tenderness and sorrow into the heart of Marian iconography.

Raphael

Known for his Madonnas, Raphael fused symmetry, grace, and warmth to present divine motherhood as both celestial and intimately human.

In works like The School of Athens, he placed spiritual philosophy side by side with classical thought, weaving the sacred into a humanist worldview.

Leonardo da Vinci

With The Last Supper, Leonardo captured psychological realism in a biblical setting, showing each apostle responding to Christ’s prophecy with distinct expressions and gestures.

His use of chiaroscuro gave divine figures subtlety and complexity, enhancing their emotional resonance.

Devotion Gets Personal

The Renaissance also saw the rise of commissioned religious works intended for private contemplation, not just public worship:

Wealthy patrons commissioned altarpieces, devotional paintings, and even frescoes tailored to their family chapels.

Art became a form of spiritual investment blending status, salvation, and personal piety.

This shift mirrored the changing relationship between the individual and the divine, one that emphasized inner reflection as much as outward ritual.

In redefining the visual language of faith, Renaissance artists brought heaven closer to earth. Their work didn’t just depict the sacred it invited viewers to feel it.

Global Religious Art Traditions

In many non Western traditions, religious art doesn’t just decorate it activates. Buddhist mandalas, for instance, aren’t just intricate patterns; they’re maps for meditation. Meant to be constructed, internalized, and sometimes destroyed, mandalas guide the practitioner through layers of consciousness. Each line and color carries symbolic intention, reinforcing the impermanence and depth of spiritual pursuit.

Islamic calligraphy approaches the sacred from a different angle. With figurative imagery discouraged in many Islamic contexts, calligraphy became the dominant visual expression of divine presence. Religious verses are transformed into elegant, rhythmic designs both a reading and a viewing experience. It’s not just writing, it’s devotion shaped by ink and form.

In Hindu temple architecture, carvings don’t whisper they shout. Packed walls filled with gods, demons, animals, and cosmic scenes all carefully ordered turn temples into three dimensional scriptures. Every figure contributes to a broader cosmic story, inviting both casual viewer and committed pilgrim to reflect on the divine in daily life.

Across the Americas and Africa, Indigenous spiritual art carries deep ancestral memory. From the Hopi katsina figures to West African ritual masks, these works aren’t “representations” they’re manifestations. Used in ceremony, dance, and storytelling, they blur the line between physical and spiritual space. Materials matter. So do the hands that make them.

In all of these traditions, iconography honors memory, shapes identity, and offers a visual vocabulary for spiritual life. Unlike Western art primarily crafted for galleries or altars, these objects often live in motion in ritual, breath, and time.

20th 21st Century and Beyond

Sacred art didn’t die with marble statues or oil on canvas. It evolved. In the 20th century, modernism cracked open the traditional forms artists like Malevich and Rothko stripped away the literal to capture the numinous. With abstraction came a different kind of reverence, focused less on idols and more on essence. Photography joined the conversation, documenting rituals, places, and figures sometimes reverently, sometimes critically and emerged as both witness and provocation.

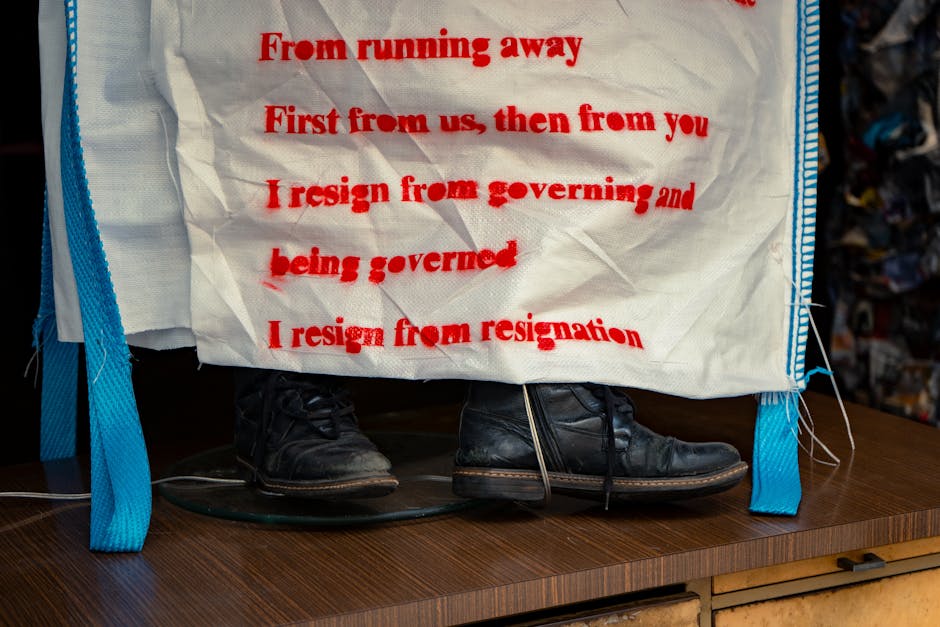

By the early 21st century, religious themes started surfacing in protest and identity art. From icon like portraits of victims of violence to mixed media altars protesting state power, creators tapped into sacred codes to express resistance and reclaim marginalized voices. Here, the divine wasn’t distant it was political, urgent, bleeding into public spaces and social media feeds.

Then came virtual chapels and digital altars. During the 2020s and into the 2030s, installation art met code. Immersive sanctuaries appeared in AR and VR. Livestreamed rituals. Prayer rooms rendered in pixelated serenity. For a generation raised online, the holy became hyperlinkable.

By 2026, AI generated and NFT based religious visuals are pushing the boundaries even further. Algorithms can now mimic Byzantine mosaics or generate entirely fictional iconographies. Some see it as desecration; others call it a democratic opening a way to reimagine what divine presence looks like under digital skies. NFTs have turned altarpieces into collectibles, rewiring not just distribution but the idea of sacred ownership. Visual theology is no longer carved in stone it’s coded, minted, uploaded, and remixed.

This isn’t the end of religious iconography it’s just another chapter. The symbols persist. They’ve just learned to render faster and run on electricity.